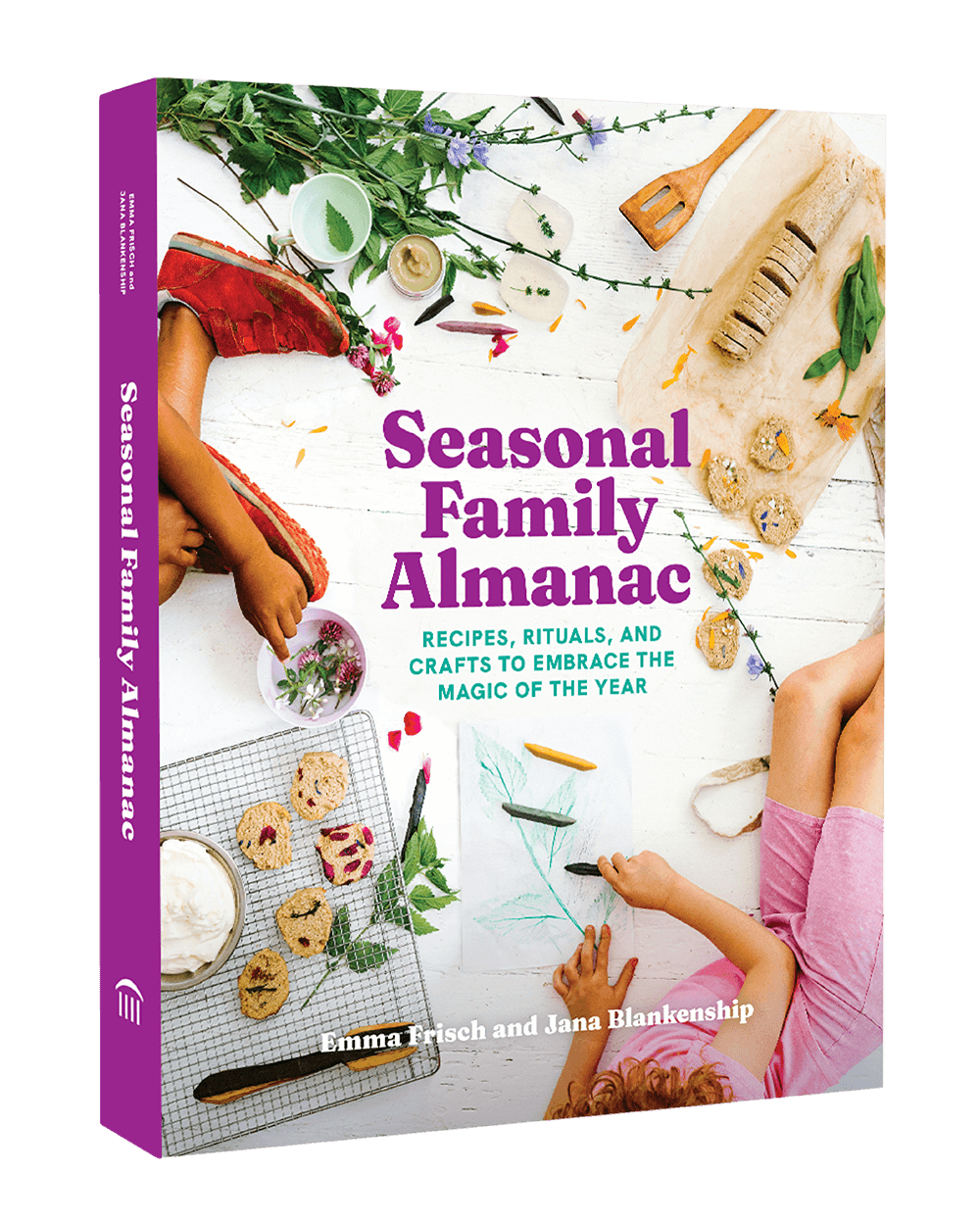

Homemade Vinegar (C’est possible!)

All it takes to make homemade vinegar is a mother. Sounds simple right? We all have mothers. Well, it’s not quite the mother you might be thinking of, but it’s still simple! Making homemade vinegar is affordable and easy as pie. It’s something I began with my real mother, the one who birthed me, and came to fine tune through a free course on Fermented Foods, offered by Ithaca’s FreeSkool and taught by the talented Rachel Firak.

I’ve only experimented with red wine vinegar, which is a handy way to sop up the dregs of a neglected bottle of wine only suitable for cooking. I’ve adapted the procedure from Rachel’s coursework, copied below with more recipes and instructions for making Fruit Vinegar, Honey Vinegar, Balsamic Vinegar, and ancient drinks like Posca and Shrub.

[If you make Kombucha at home, this will be second nature.]

WHAT YOU’LL NEED & HOW TO MAKE VINEGAR

A vessel

A clean glass jar or food-safe glazed ceramic crock. I like starting with 8 oz jars, and graduating to bigger jars to accommodate my growing batch of vinegar.

The “mother”

So what is this mysterious mother? In a simplified description for the non-science savvy (like me!), a “mother” is a naturally occurring film that forms on the top of liquid as a result of chemical reactions between sugar, wild yeast, bacteria, acetic acid, alcohol, and carbon dioxide. Except for sugar, all of these products can be harvested from the air around you. However, to help speed things up, you can find the initial stages of a mother in a natural vinegar product like Bragg Apple Cider Vinegar. Their website provides a nice description here:

“Natural (undistilled) organic, raw Apple Cider Vinegar (AVC) can really be called one of Mother Nature’s most perfect foods. It is made from fresh, crushed apples which are then allowed to mature naturally in wooden barrels, as wood seems to “boost” the natural fermentation. Natural ACV should be rich, brownish color and if held to the light you might see a tiny formation of “cobweb-like” substances that we call the “mother.” Usually some “mother” will show in the bottom of the ACV bottle the more it ages. It never needs refrigeration. You can also save some “mother” and transfer it to work in other natural vinegars. When you smell natural ACV, there’s a pungent odor and sometimes it’s so ripened it puckers your mouth and smarts your eyes. These are natural, good signs.”

Raw vinegar (from the mother’s vinegar)

Pour about 1/3 cup of vinegar, like the one mentioned above, along with the newly formed mother into your clean vessel.

Red Wine

Whenever you have a bit of leftover wine, pour it into the crock. Do this by sliding the mother aside with a clean utensil, and pour the wine in. If you pour the wine on top, the mother might sink and lose her vinegar-making abilities. (However, my mothers sunk because I did not follow these instructions and I still have vinegar!)

A piece of cotton cloth and a rubber band

This is for keeping out fruit flies and other unwanted organisms. The cloth should be breathable but prevent critters from crawling in. Cover the crock with cloth and a rubber band.

Raising your vinegar

Feed your jar or crock with more small quantities of wine every few weeks. When the crock is full, taste occasionally until the acidity is to your liking, then harvest the vinegar.

For best results, start with a small container and an established mother. Add wine a little at a time, to give the “mother” a chance to recover after each addition. But don’t pour wine directly on the mother (the alcohol may create a barrier between the acetobacter and the oxygen it needs to work). Gradually move up to larger containers as your stash grows; filling your container might prevent other microorganisms from growing on the sides of your container, which could (rarely) introduce contamination problems.

Harvesting your vinegar

You can also try the vinegar when the jar is not full. If you like the taste, pour some out to use on a salad! You can use the vinegar as it’s aging.

Disclaimer: I am not a professional nor an expert on fermentation or making vinegar. However, making vinegar has been practiced in households for centuries, worldwide. Many fermentationists would argue that fermented foods are filled with immune-building and nutritional microorganisms, and that there is too much skepticism around food safety with fermented products. Please make sure you advise and educate yourself when preparing and eating anything at home.

Check out Cooking Detective’s 23 Health and Wellness Benefits of Apple Cider Vinegar.

____________________________________________________

MAKING VINEGAR

By Rachel Firak

Vinegar is a two-part ferment:

Part 1. Convert sugar to alcohol using yeast.

Part 2. Convert alcohol to acetic acid using bacteria (acetobacter).

You can start from scratch by making sugary fruit into alcohol and alcohol into vinegar, or you can pick up at part 2 by using alcohol, like wine, to make your acetic acid.

WHAT YOU’LL NEED:

A clean glass or food-safe glazed ceramic

A sugar source: Fruit, organic evaporated cane juice, GMO beet sugar, molasses, “boiled cider”, maple syrup, honey- anything will do. Honey will slow down the fermentation process.

Water: Chlorine kills bad and good microorganisms. If you have chlorinated water, let it sit loosely covered overnight to let the chlorine evaporate.

A yeast starter: Something that contains live, active yeast. Raw fruit peels. Raisins. Whey. Commercial yeast. A pinch of another live, yeasty, fermented food (raw sourdough starter, microbrewery beer, homemade wine*). Or catch wild yeast from the air.

An acetobacter starter: Raw, unfiltered vinegar. A piece of a “mother of vinegar” – a naturally occurring product that contains acetobacter and cellulose made by the acetobacter. A kombucha SCOBY (Symbiotic Colony Of Bacteria and Yeast). A wooden container that has held vinegar recently. Or catch wild acetobacter from the air.

A cloth: Something to let air (and thus wild yeast and acetobacter, and the products they need to flourish) in, but will keep fruit flies out.

* Commercial alcohol will not work as a yeast starter because it is sterilized before bottling.

RECIPES

Fruit Scrap Vinegar (adapted from Wild Fermentation by Sandor Katz)

Dissolve 1/4 cup sugar in 1 qt water. Pour it over about 2 cups of raw fruit scraps in a glass jar. Cover with a clean kitchen towel and secure with a rubber band. Leave it at room temperature in a dark place for a week. Strain out the fruit and discard. Ferment the liquid 2-3 weeks more, stirring or agitating periodically. A mother should form on top. Strain out when done or leave it in. Store at room temperature.

Honey Vinegar (from Putting It Up With Honey by Susann Geiskopf-Hadler)

Mix together 1 quart of filtered honey and 8 quarts of warm water. Cover with cloth and secure with a rubber band. Allow mixture to stand in a warm, dark place until fermentation ceases (about 2 months). The vinegar should be clear in color. Test for acid strength. When strong enough, strain and seal in clear, sterilized jars.

Molasses Vinegar (from Putting it up with Honey by Susann Geiskopf-Hadler)

Mix 1 quart molasses and 4 ½ quarts water thoroughly. Pour into a crock, allowing 20% headspace (space between the top of the container and your liquid). Cover crock with cloth and secure with a rubber band. Place in a warm, dark place. Let work for 2 months and test. When strong enough, strain and bottle.

Wine Vinegar

Keep a dedicated wine vinegar crock in your kitchen. Add some raw vinegar (with the “mother”) or an established mother of vinegar from a friend. Whenever you have a bit of leftover wine, pour it into the crock. Cover the crock with cloth and a rubber band. Feed with more small quantities of wine every few weeks by sliding the mother aside and pouring in wine. When the crock is full, taste occasionally until the acidity is to your liking, then harvest the vinegar.

For best results, start with a small container and an established mother, and add wine a little at a time, to give the “mother” a chance to recover after each addition. Don’t pour wine directly on the mother (the alcohol may create a barrier between the acetobacter and the oxygen it needs to work). Gradually move up to larger containers as your stash grows; filling your container might prevent other microorganisms from growing on the sides of your container, which could (rarely) introduce contamination problems.

Malt vinegar

See Wine Vinegar; use beer instead of wine.

Balsamic vinegar

Balsamic vinegar is made by using the aging process below, but it begins by pouring “must” into the barrel instead of vinegar. Must is made by slowly boiling fresh grape juice down over the course of a day until it has reduced by half. If you want to try this, you may have to add yeast starter to kick off the fermentation process once the must cools to lukewarm, because the heat will have destroyed the natural yeast. However, this will not be necessary if you have barrels that have been used to make vinegar for years, in which case the microscopic cracks in the wood on the inside of the barrel should have all the microbiodiversity you need to produce great vinegar. Leave your barrels in an attic or an area where they get cooler (but not frozen) in the winter and warmer in the summer.

PERFECTING & USING YOUR VINEGAR

Aging your vinegar: for true connoisseurs

It is generally accepted that aging vinegar produces the best results. In order to do this, you will need several (5-7 is traditional) barrels of graduated size, big to small, and made of wood (oak, ash, chestnut and cherry are some possibilities¥). First clean them with strong vinegar, salt, and water and rinse thoroughly. Then start the process by filling the biggest one with “fresh” vinegar, covering the barrel’s bunghole with cloth to allow for some air circulation. Some of the vinegar will evaporate over time; this is the “angel’s share.” Wait a year, then move the vinegar from the biggest container to the next largest one and fill the biggest one with fresh vinegar once more. Usually all of the vinegar from the biggest barrel will not fit into the next largest barrel; that’s OK. Leave the remainder to mingle with the newer vinegar you pour in. Every year, move each barrel’s contents into the next barrel down the line. The biggest one is the only barrel that ever receives new vinegar. The aging process can be halted at any time or can continue for decades.

¥ If you don’t have barrels (it is 2012, after all), you can also use glass or food-safe ceramic containers and add wooden cubes to them to produce good flavor.

Sterilizing your vinegar

To sterilize your vinegar, killing off all the microorganisms and halting fermentation at an acidity you prefer, pack the vinegar into canning jars and waterbath can them, heating to boiling on the stove and leaving there for 10 minutes before removing to let seal. This is optional; some say raw vinegar confers many health benefits.

Pickling with your vinegar (from Indiana University’s CWA union)

Editor’s note: Pickling with homemade vinegar isn’t recommended because vinegar used in pickling must be very low in pH, and accurate pH tests aren’t cheap. Pickling with higher pH vinegar will not properly prevent spoilage or contamination with dangerous microorganisms like botulism. However, if you plan to do it anyway, this is a way to make it safer.

The following steps are optional unless you want to pickle safely with your vinegar. You will need to test the acidity of your vinegar in one of two ways. One way is to use storebought pH Strips₴ before sterilizing it. The other option is to use a scale and an eye dropper like so. Measure out a few grams of baking soda in a small bowl on your scale. Then fill an eye dropper

with distilled vinegar and put a drop on the baking soda. When the bubbling completely ceases put another drop on the baking soda. Repeat until there is no bubbling at all. Note how many drops this takes. Then do the same with your home made vinegar. If it takes less of your vinegar to reach a non bubbling state with the baking soda, then your vinegar is acidic enough to safely pickle with.

₴ Editor’s note: pH strips are not known for being particularly accurate. Please be careful.

TROUBLESHOOTING

Does vinegar go bad?

Yes, but probably not in the way that you’d think. Sub-par, tasteless or weak vinegar can be caused by improper storage. When you leave a container open for a very long time (months or years), the acetic acid eventually turns into carbon dioxide and water, leaving an unappetizing solution behind. Some people say that if you make or store your vinegar in a well-lit place, you could end up with a less than tasty product. So cap your vinegar tightly and store in a dark place. In any case, unless you observe an unwanted guest in your vinegar (see below), it is probably safe to consume.

What’s growing in my vinegar?

Learn to distinguish the difference between the good guys and the bad guys in your vinegar zoo. Mother of vinegar resembles a jellyfish floating on the top of your liquid. Yeast can look like brown, cloudy strings floating around, or sediment collecting on the bottom of the container. These are the good guys, and can be used to speed up the vinegar making process in a new batch. Then there are some neutral characters that sometimes appear: vinegar mites that live in the cracks in vinegar barrels, vinegar eels or nematodes that shake their little flagella when disturbed, and fruit fly larvae, which look like tiny worms crawling up the side of your container. These things, while disturbing, do not harm your vinegar. Strain them out, wash your container and continue. Bad signs include brightly-colored or black mold (fuzzy coating on the surface) or a bad smell (like cleaning fluid). This indicates contamination, probably caused by not cleaning your vessels properly, not storing your container properly (don’t let it experience extreme or prolonged periods of cold, for example), or simply being unable to propogate a strong, healthy colony of yeast and acetobacter in the face of competition. You should probably throw this vinegar away.

VINEGAR DRINKS

Posca

Thousands of years ago, lower class Roman soldiers had to drink vinegar mixed with water instead of wine. The acid may have purified suspect drinking water. Recipes for this ancient drink are largely speculative. One approximation is:

1 ½ cups vinegar

½ cup honey

1 tablespoon crushed coriander seed

4 cups water

Dissolve the honey in hot water and let cool before mixing with vinegar. Strain out the coriander seeds and serve chilled.

Switchel

Also called “Haymaker’s Punch,” this drink quenched the thirst of American farmers in the fields during hay season. As Laura Ingles Wilder wrote of this drink she called Ginger-water, “Ginger-water would not make them sick, as plain cold water would when they were so hot.”

(1 ½ – 2 quart recipe)

1/2 cup apple cider vinegar

Sweetener to taste (molasses, maple syrup, honey, sugar- the traditional recipe, which is sweet, is 1/4 cup molasses and 1/2 cup honey or sugar)

1 1/2 teaspoon ground ginger or ⅓ cup grated fresh ginger

Water

Optional: a small amount of oatmeal (for body and flavor)

Combine all ingredients in a jar or glass. Add enough water to double the recipe for a flavorful drink, or twice that amount for a mild thirst quencher. Cover and refrigerate at least 2 hours and up to a day. Shake or stir before serving. Taste and adjust sweetener, if desired. If using fresh ginger, strain through a fine sieve or cheesecloth. Chill on warm summer days, serve hot on cold winter nights.

Shrub

Also called “Drinking Vinegar,” shrub (from the Arabic word sharab, to drink) is a beverage that peaked in popularity in the 19th century.

(1 ½ – 2 quart recipe)

1 cup fruit or fruit preserve

1 cup vinegar

Sweetener to taste (molasses, maple syrup, honey, sugar)

Sparkling water to serve

Crush fruit, add vinegar and stir to combine. Cover and refrigerate for at least 24 hours, occasionally shaking/stirring the contents. The next day, give the mixture one last good shake or stir and then strain using a fine-mesh strainer and/or cheesecloth. Discard the solids. Measure the liquid. Add sweetener to taste. If using dry sugar, create a simple syrup by combining sugar 1:1 with water and bring to a boil for 5 minutes over medium-low heat, stirring, and let cool before combining with other ingredients. Bottle and chill. To serve, mix with sparking water. Start with 1 part shrub to 3 parts sparkling water and adjust to taste.